The television will be revolutionised

Pluto TV has the potential to change the balance of power in Australian television. Plus Buzzfeed's bust; adland's predators and the Kinderling sale to SCA

Welcome to Unmade, mostly written in rainy Horsham, while you were sleeping on Thursday morning.

Happy Pretend to Be A Time Traveller Day.

As I mentioned earlier in the week, at this stage of figuring out what Unmade is, my plan is to publish two longer, more analytical pieces per week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. So this will be part of that new rhythm.

Today’s edition is for paying subscribers. Those who haven’t signed up to the paid tier of Unmade will hit a paywall further down this article.

For the next nine days only, an annual subscription to the paid tier of Unmade is available for just $169, a saving of 74 per cent on the normal $650 price. That will never be as low again.

Today: What Ten’s plans for Pluto TV say about the state of the television market; Buzzfeed’s float flop; SCA’s Kinderling purchase; and harassment in adland.

Planet Pluto

Initially, I thought I’d found an original headline for today’s newsletter. Remember the Gill Scott-Heron song The Revolution Will Not Be Televised?

It turns out I’m not the first to have thought of it. Google offers more than 1,500 links to articles containing the phrase or headline “The television will be revolutionised”. And another 1,600 links to the phrase “The television will not be revolutionised”, including the time I used it on Mumbrella back in 2015. If you’re going to plagiarise, you might as well do it to yourself.

On that occasion, I was analysing the emerging view that the television industry might not suffer the catastrophic consequences digital media was wreaking on newspapers and magazines. Broadly, that has indeed been the case, even if broadcast audiences aren’t what they used to be.

Take last Sunday, for example. There was not a single TV show broadcast to more than a million viewers. According to OzTam, the most watched program of the day was Seven News, with an average of 936,000 viewers across the five capital cities.

Compare that to a decade ago. Seven’s top rating Sunday night news bulletin was delivering at least 1.3m, at least 30 per cent more viewers than now. And in a big week, Sunday entertainment shows could draw 2m overnight metro viewers.

That was before the arrival of the subscription streaming services, which kicked off seriously in early 2015 with the launches of Stan and Netflix. Has it been nearly seven years already?

However, although that meant more competition for viewers’ attention in an already fragmenting media landscape, the absence of advertising on the streaming platforms meant that television’s commercial dynamic was hardly affected.

But now the rise of ad-supported video on demand is finally starting to have a real impact. And next year’s launch of Pluto TV, by Ten’s owner ViacomCBS - revealed in yesterday’s Unmade podcast - has the potential to change the balance of power.

Over the last decade, Ten - always the third player - has fallen further behind as it slowly recovers from the strategic void created by Lachlan Murdoch’s failed attempt to take control.

Wider trends are now coming into play. And they will rewrite the game.

If the launch of Pluto is as well executed as it has been in other markets, the company will rejoin the current two-horse race between Nine and Seven for screen dominance. Indeed, there’s every chance that the company could emerge as the dominant player in ad-supported video on demand (AVOD).

Viewers have surprised even the TV networks with their appetite for AVOD.

The rise of the subscription services was predictable before they launched locally. Netflix’s overseas success made clear that consumers saw the value in subscribing to a library of content rather than having to buy or rent. The threat at this stage seemed to be more to the premium priced Foxtel broadcast offering.

Less of a surefire thing was how the existing commercial players would fare as they moved into streaming themselves.

And just as streaming divides between the subscription and the ad-supported services, for the big commercial players AVOD then splits between “live” and on-demand.

I put “live” in quotation marks, because this terminology is being used by the industry to refer to streaming of the network channel as it airs.

And on-demand viewing has included both catch-up viewing of recent network content, and library content.

The terminology is ever-changing, by the way.

If you listen to yesterday’s podcast with Ten’s Rod Prosser, he gently corrected me at one point, to say the industry’s preferred terminology is now AVOD, rather than catchup.

In turn, another TV executive I spoke to after uploading the podcast chided me for using the term AVOD, saying the commercial TV players in fact prefer BVOD, for broadcast video on demand, because this distinguishes them from the likes of YouTube’s user-generated content.

And Prosser’s ultimate boss, ViacomCBS’s global president and CEO Bob Bakish, now prefers yet another acronym: FAST - standing for free ad-supported streaming television.

There’ve been a couple of surprises on how it’s unfolded.

First, the networks have been surprised by how much of their AVOD viewing has indeed been of the live channel, from viewers on devices, or even on smart TVs that might or might not have an aerial input.

That’s bad news for the regional TV players, by the way. As the “great geoblock of Woolongong” test case in 2016 proved, the metro networks can stream their content throughout the country, not just in their own licence areas. Nine’s regional affiliate WIN Corporation had tried to stop the company from doing so but lost the case.

Given the rate of take up, the timeline to the end of a broadcast TV signal is looking shorter than anybody would have predicted. Just as new home owners increasingly don’t bother to install a landline for their phone, householders soon won’t bother to install or replace rooftop antenna.

It will take a while, but at some point, to Australia’s commercial TV players, AVOD will be everything.

Which is where the arrival of Pluto TV gets really interesting.

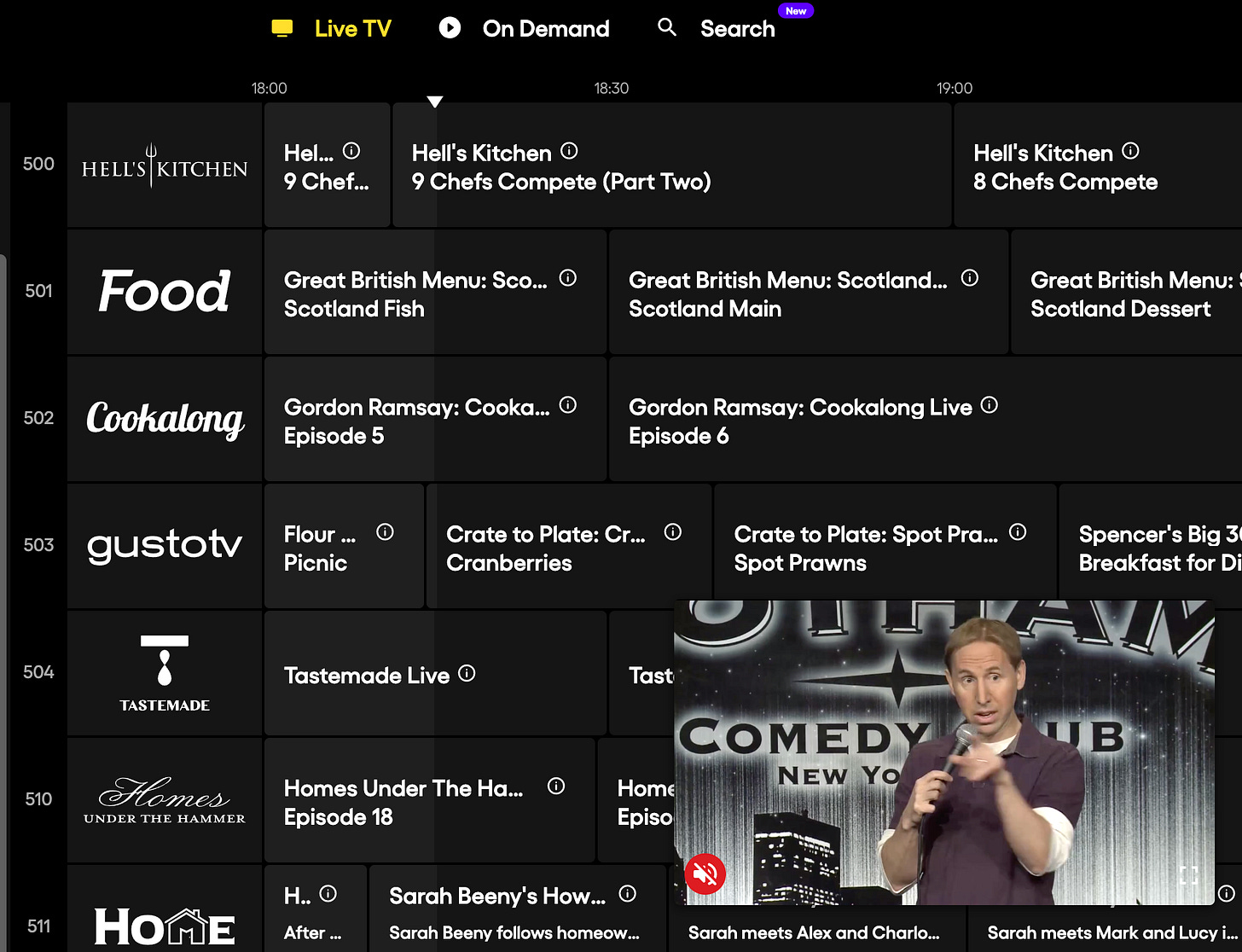

Although it offers on demand content, Pluto’s main navigation prioritises live channels, and a lot of them. It’s available on the web, on mobile apps and on smart TVs.

In the US, Pluto TV offers more than 200 channels, in the UK more than 150. I paused writing this to have a look what was going out on Monday evening, London time.

You name the genre, and they’re there - factual (think Mythbusters reruns); documentary (Super Size Me); crime (The FBI Files); entertainment (the Duck Dynasty Channel); drama (McLeod’s Daughters). There’s standup comedy. There’s news. There’s extreme sports. There’s even a Cats 24-7 channel. Yes, really.

And all with a light ad load - lighter than broadcast television.

Much of the content is ancient stuff from the archive, but well curated. I’d be surprised if Pluto TV doesn’t launch in Australia with a 24-7 Neighbours channel, for instance.

You can get a more comprehensive explainer of the Pluto viewer experience on Dan Barrett’s Always Be Watching, by the way.

And curation is the key to the Pluto TV model. Back before streaming, I’d be flicking channels and come across a movie and happily start watching it, even though I already had it sitting on a DVD on my shelf.

The Pluto navigation is unlike Australia’s existing players. The nearest equivalent would be Fetch TV’s navigation.

Although Seven has already begun to pursue a genre strategy in its AVOD service 7Plus, it’s not offering the Pluto-style of emphasising channel content.

About four hours ago, I watched a live stream of Bakish speaking from New York to a UBS Global conference.

He talked about the attraction to viewers of Pluto as being a “sit back” experience.